This blog is about the virtual reconstruction process of the abbey of Ename in Belgium. As many people have little knowledge about how and why a virtual reconstruction is made, we show in this blog the detailed process of the creation of the virtual reconstruction of this abbey and how this abbey evolved through time from 1065 to 1795. So this blog is a way to document this process in a good-looking and readable way, not focusing on the pretty pictures but on the sources, on the interpretation process and on the methodology of this process. To get a better understanding of virtual reconstruction, let’s have a look of how this activity emerged in the last 30 years, and which goals the pioneers of virtual reconstruction pursued.

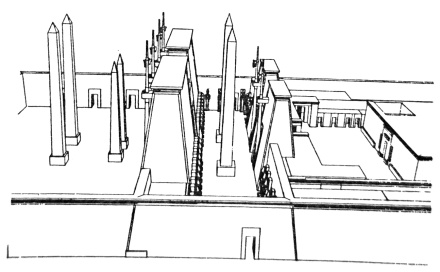

Since the 1980s, 3D modelling software has been used to visualise archaeological remains and make hypotheses about historical buildings or structures that got destroyed or incorporated in later structures. One of the first people to apply this 3D modelling was Robert Vergnieux, who was working as an archaeologist in Karnak, Egypt in 1985. He used the 3D modelling software PDMS to make virtual reconstruction of the temple of Amon-Re at Karnak, based on archaeological research. Robert Vergnieux is currently leading ArchéoVision.

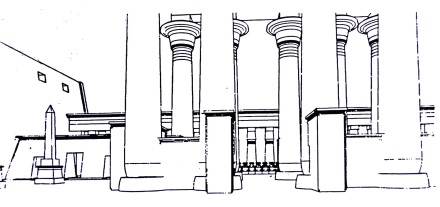

Temple of Amon-Re at Karnak in the time of Hatshepsut by Robert Vergnieux (1985)

Kiosk of Taharqo at Karnak by Robert Vergnieux (1985)

Initially, in the late 1980s, the Department of Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and archaeologist Timothy Kendall began to work with (the late) Bill Riseman on creating simply shaded and wireframe 3D computer models of the site and the major buildings of Gebel Barkal (Sudan).

Driven by the domains of commercial advertisement and CAD, computer graphics is developing fast in the second half of the 80s. In 1989, the French company Ex Machina contributes to a shortfilm “1789” with virtual reconstructions of Paris in 1789.

In 1992, the Centre d’Enseignement et de Recherche ENSAM, sponsored by IBM, used a CATIA CAD system to create the medieval church of Cluny (France). ENSAM has created several units that work with 3D and virtual reality, such as the MAP-Gamsau lab in Marseille.

In the period 1991-1993, 3D computer graphics went through a real revolution and became an established technique in different domains such as film and computer games.

In 1996, classical archaeologist Bernie Frischer founded the UCLA Cultural Virtual Reality Laboratory to use 3D virtual reconstructions in his research about Rome. He also used 3D visualisation as a support while teaching his courses on Roman archaeology and architecture. The reconstruction effort resulted in the Rome Reborn project, showing Rome in 320 AD, based upon virtual reconstructions by a large number of experts. The most recent visualisation of this outstanding 3D model has been made by NoHo and is called Rome320AD.

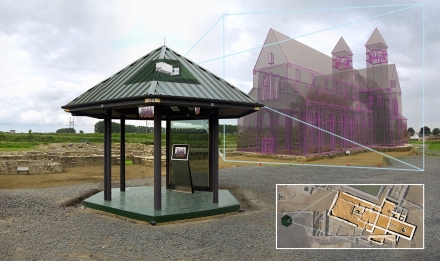

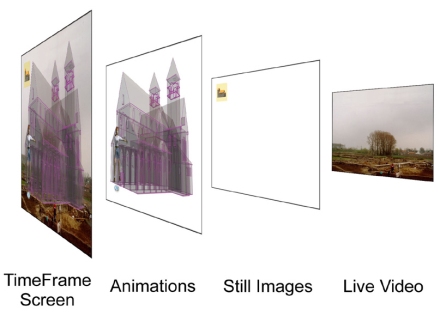

In 1996, the Ename TimeFrame was conceived by ir. Daniel Pletinckx, as an augmented reality solution for the archaeological park of Ename, Belgium, based on ideas of archaeologist Dirk Callebaut and designer John Sunderland, developed at a workshop of the Getty Conservation Institute. The system was developed by the team of Ian Holden at the IBM research labs at Hursley, UK. The system was inaugurated in September 1997 and remained operational until 2005. This blog shows, amongst many other subjects, the making of the content of the new TimeFrame, inaugurated in 2013, using the original hexagonal housing. The 1997 system used a live video stream of the archaeological site and showed an augmented view by superimposing virtual reconstructions of the abbey buildings on top of the live video. The system also showed animated virtual reconstructions of the site and the inside of the Saint Salvator church together with images of the excavations.

In 1997, Donald Sanders founded the company Learning Sites with the aim to revolutionize public education and scholarly research in the field of archaeological visualisations, and to digitally preserve archaeological data that is languishing and actually deteriorating in existing archives. Donald Sanders started amazing initiatives such as the the Institute for the Visualisation of History that provides 3D reconstructions as educational resources.

Virtual 3D model of the excavation of the Halieis House in Greece (by Vizin)

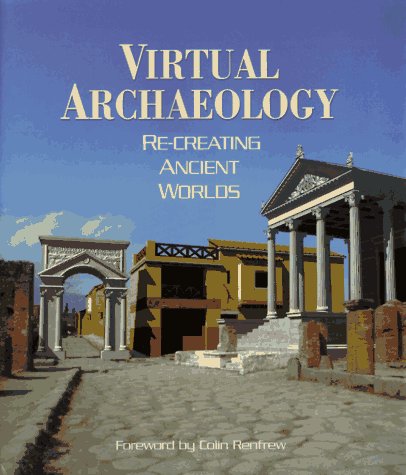

Also in 1997, Maurizio Forte compiled the book Virtual Archaeology, listing many examples of early virtual reconstruction projects in Pompeii, Crete, Xi’an, Giza, Mycenae, Stonehenge, Abu Simbel, … This book was an eyeopener to many people, both in cultural heritage and ICT. Maurizio Forte was heading for many years the Virtual Heritage Lab of CNR, which is today still playing a leading role in research and projects for digital heritage. Today, he is professor at Duke University, USA.

In 1998, a virtual reconstructions of the city of Delft in 1660 was made at the TU Delft. The reconstruction refers to the famous painting of Vermeer but is based upon historical maps by Frederik de Witt, Joan Blaeu (1649) and Johannes Janssonius (1657).

In 1996, A Research Doctorate in History and Information Technology was established at the University of Bologna, in order to promote experimentation in the use of new technologies for historical research. As a result of that, CINECA made in 1999 one of the first virtual reconstructions of the evolution of a historical city. The NuME project reconstructed the city of Bologna, based upon a well defined methodology.

Throughout this history of virtual reconstruction, we see that many of its pioneers have focused on its role as a methodological interpretation of the past. Although virtual reconstruction of historical man-made structures and landscapes has its roots in film and advertisement, it definitely is a scientific activity. But it also has the potential to produce stunning images, great educational resources and interactive applications, both in museums and online. Nevertheless, virtual reconstructions do not reconstruct the past, they show what we know of the past! And although we know certain things very well and for other things, we nearly have no information, we still need to create a consistent image, something that could have existed and is the most probable, given the information we have.

So, how are virtual reconstructions made? Virtual reconstructions rely on a wide variety of sources, such as excavation reports, geophysical scanning, historical research, iconography or studies of historical landscapes . But also less evident sources are available from experimental archaeology, hydrography, anthropology, even from re-enactment and physical reconstruction. For example, the Roman city of Carnuntum at the Donau river (in what is today Austria) has both virtual reconstructions (in the museum and online) and physical reconstructions (in the archaeological park). The physical reconstructions have been made under supervision of a team of experts, and had to deal with a lot of issues on how to make them “work”, so they are very valid sources of information for the virtual reconstruction process. Carnuntum also has a digital database of objects found at the archaeological site. These objects can be downloaded and used in virtual reconstructions, so they are another potential, high quality source for virtual reconstructions and visualisations.

First of all, all these different sources are collected, documented and assessed for their reliability and quality. Secondly, they are correlated (compared to each other) to find reliable information. If for example a historical source gives information that is confirmed by an archaeological source, then this information has a higher probability than if the information only comes from one source only. If specific information is missing, it potentially can be filled in through comparison with similar sites or contexts, but this information will have a lower probability. On the basis of the available information, several hypotheses are made, which are ordered from the highest to the lowest probability. The hypothesis with the highest probability is taken as the proposed virtual reconstruction, completed with the most probable missing elements to make the reconstruction consistent and realistic. For example, if you reconstruct a medieval harbour, you have to put the correct ships in that harbour, even if you have no historical or archaeological sources that prove which ships have frequented that harbour. This process has been described in detail in this publication, which is based upon the London Charter, that provides the internationally endorsed guidelines for virtual reconstruction, made by early pioneers such as Richard Beacham, Franco Nicolucci and Bernie Frischer, supported by the excellent work of Hugh Denard and Drew Baker.