As we have explained in the previous blog post, the Ename crosier is the ivory head of an abbot’s staff and has been excavated in 1995 at the archaeological site of Ename, Belgium. This outstanding object has suffered damage in several ways, so it makes sense to find out in this second blog post how the crosier looked like in its original state. A third blog post will reconstruct how it turned into its current broken state. The fourth and final blog post about this Flemish Masterpiece will talk about its symbolism and unique character.

Detail from the Evangiles de Liessies (1146) showing a 12th century abbot’s staff

First of all, the crosier is only partial and has been broken, so that the staff and the part that connected this top part with the staff itself is missing. In the publication about the crosier by Elisabeth den Hartog, the hypothesis is put forward that this staff has been buried with a deceased abbot at the end of the 14th century and has been unearthed by grave robbers at the end of the 16th century, when the abbey was in ruin and the country in state of civil war, causing massive poverty. As the crosier cannot be in a broken state when used as a burial gift, it is plausible that the grave robbers have broken the object, causing additional deformation and damage (both hands of the Saint Saviour figure, and the lily and left hand of the lady have been broken). Unlike gold or silver, ivory cannot be reused easily, making the object worthless for the grave robbers, who discarded it. We will expand on this in the next blog post.

The 12th century Ename crosier, made in ivory (photo: pam Ename)

Secondly, parts of the object are corroded, due to being buried – probably in a grave – for about 400 years. This corrosion has erased some of the interesting fine details of the crosier, such as the head of the dragon or the text on the side of the lady.

Most of the Lady side of the Ename crosier shows corrosion of the ivory (photo: pam Ename)

Finally, the crosier must have been broken and repaired during its active use. The two bronze bars that traverse the object horizontally have been added to keep the broken pieces together. Unfortunately, the man who repaired the crosier had to cut away the top jaw of the dragon to make the lower bar fit. The lower jaw must have been broken by the grave robbers. We will discuss this in the next blog post.

The dragon has both upper and low jaws missing (photo: pam Ename)

Some years ago, the crosier was 3D laser scanned in high resolution. Assessment of the 3D data shows a resolution of about 50 micrometer, 1/20 of a millimeter. Based on this 3D scan, we have decided to perform a digital restoration of the crosier, to be used in Eham 1291 (the new version of the Ename 1290 educational game) but also to be 3D printed for the educational department.

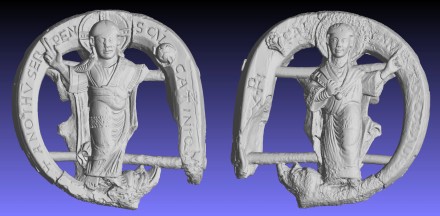

The highly detailed 3D scan of both sides of the crosier (image: Visual Dimension bvba)

Digital restoration is a form of virtual reconstruction and tries to show how an object looked like in its original state and how it was probably used. In digital restoration, we try to unravel the many clues that are hidden in the object itself, but also look at similar objects, at the time period it was made and used and at the alterations that were made. We collected about 200 similar medieval crosiers and about 500 images from medieval manuscripts to base our reconstruction on. Here is the result, in 3D, and how we did it. Use the annotation bar at the bottom to get a guided tour through the applied restorations

Most of the digital restoration of the broken parts (cracks, broken wrists, lily staff, corrosion) and the repair (removal of the bronze bars) is quite straight forward. The lily staff for example, which is the medieval symbol of virginity, can be seen depicted in medieval manuscripts. The hard parts are the restoration of the text on the lady side, the dragon and the missing part of the crosier that connects it with the staff.

The bride of Christ with the lily staff as symbol of virginity (Yale MS 404, f50r, ca. 1300)

The bride of Christ holding the lily staff as symbol of virginity (image:Visual Dimension bvba)

The interpretation that the lady is the “bride of Christ” and not our Lady is taken from the above mentioned text by Elisabeth den Hartog.

Macro image with large depth of field through image stacking showing the text on the lady side (photos: pam Ename, image processing: Visual Dimension bvba)

The text on the Lord side is intact and nearly complete, it reads

+AN(IM)O IH(ES)U SERPENS CALCAT(UR) INIQU(ITATIS)

which means “Through the spirit of Jesus, the snake of the evil is being trampled” (text between round brackets is typically omitted in medieval writing).

The digital restoration of the text on the Lady side does require an optimal interpretation of the object (based upon the 3D scan) and its symbolism (based upon the detailed art history study). In the publication by Elisabeth den Hartog, the inscription is interpreted as

… CHR(IST)I CALCANTIS MALA D[ELENTUR]

based upon photographs of the objects (text between square brackets is an interpretation). The 3D scan (see above) and a detailed study of the real object, including focus stacking macro photographs of the text area, however revealed that MALA needs to be read as COLLA, so the text can be interpreted as

[SP(ON)SA] CHR(ISTI) CALCANTIS COLLA DR[AC(ONIS)]

which can be translated as “The bride of Christ, trampling the neck of the dragon”

Both sides of the digitally restored crosier, showing the reconstructed text (image: Visual Dimension bvba)

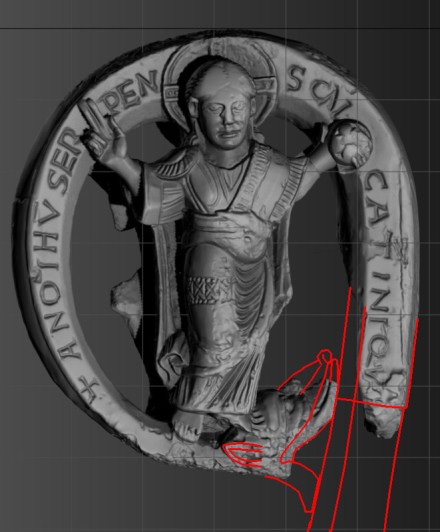

For the restoration of the dragon, we found multiple evidence in the 3D model that the dragon is biting the crosier, so that the neck of the dragon is well connected to the vertical part, providing the object some sturdiness and making the cutting of the ivory feasible (i.e. reducing the risk of breaking while cutting).

Design of the missing parts of the dragon, providing sturdiness and feasibility (imge: Visual Dimension bvba)

There is plenty of medieval iconography that shows dragons and biting dragons, giving hints towards the digital restoration. To have a sufficient contact surface of the lower jaw with the vertical shaft, we have given the dragon a beard, as can be seen in many medieval depictions of dragons.

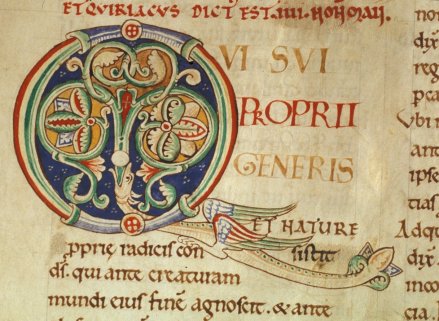

Illuminated capital in Harley Ms. 628, f. 101v (British Library)

Bearded dragon on a German 13th century crosier (Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY)

Comparison with the large set of crosier images showed that the missing part of the crosier follows the curved line, putting the decoration of the crosier at an angle to the vertical line of the staff.

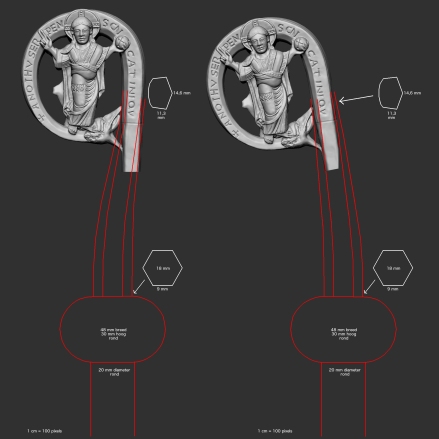

Initial (left) and final (right) design of the missing part of the crosier (image: Visual Dimension bvba)

From iconography and preserved staffs, we know that the complete staff was about 180 cm high, ending in a metal point.

Two abbots with their staff (Moralia in Job – 1110 – Bibliothèque municipal de Dijon)

We have no information if the staff itself was in wood or in ivory, both alternatives are possible, so we presume the staff to be in wood. We have gold-plated some parts as this was a common practice in the Middle Ages for ivory crosiers. XRF measurements could tell us if gold was applied on the object, but such measurements are not available yet.

Reconstructed staff with iron pin at the end (image: Visual Dimension bvba)

The final result was 3D printed in polyamide on scale 1/1 so that it could be mounted on a wooden stick, for the educational department. The digital restoration was performed through digital sculpting by Ewout De Vos for Visual Dimension bvba.

Ewout De Vos holding the digitally restored crosier next to the real object (photo: Visual Dimension bvba)

This work has been partially funded by the Flemish Ministry of Culture.