One of the periods in the Ename abbey history that we know very well is the time that Antonius De Loose acted as abbot. He was a genuine manager who left us many documents, that help us today in the virtual reconstruction of this period. We know the life of Antonius De Loose quite well, from a number of sources, but we only have one image of him. He became abbot of the Ename abbey in May 1657.

The only known depiction of abbot Antonius De Loose (Jan Bale, 1658)

As an abbot, De Loose left us a manuscript with the rules of the abbey (written in 1667 and published in 1999), his personal diary over the period 1671-179 (published in French by C. van den Haute in 1921) and a number of letters written to Pieter Hemony, who produced the carillon of the abbey (published by the Dutch carillon expert André Lehr in 2004). He commissioned also other documents, such as maps of the abbey properties, which are today of paramount importance to reconstruct Ename and its evolution since the 10th century. The creator of these maps was surveyor Jan Bale from Ghent.

A self-portrait of Jan Bale in 1658

Jan Bale himself depicted this mapping process in a painting preserved today in the castle of Olsene, Belgium. The scene shows us abbot De Loose (standing), Jan Bale (seated in the middle) and his team of surveyors. The painting is signed by Jan Bale and dated in 1658. On the table, new maps are being drawn and coloured. Surveying equipment and documentation are lying on the floor. Abbot De Loose is supervising the work.

The team of Jan Bale working in the Ename abbey (Jan Bale, 1658, painting currently at the Meheus castle in Olsene, Belgium)

The maps that this team made are preserved today, both as drafts and in a final version, in the Beaucarne House in Ename. These maps show in detail the abbey properties in the neighbourhood of Ename. The colours depict the different property rights of the parcels.

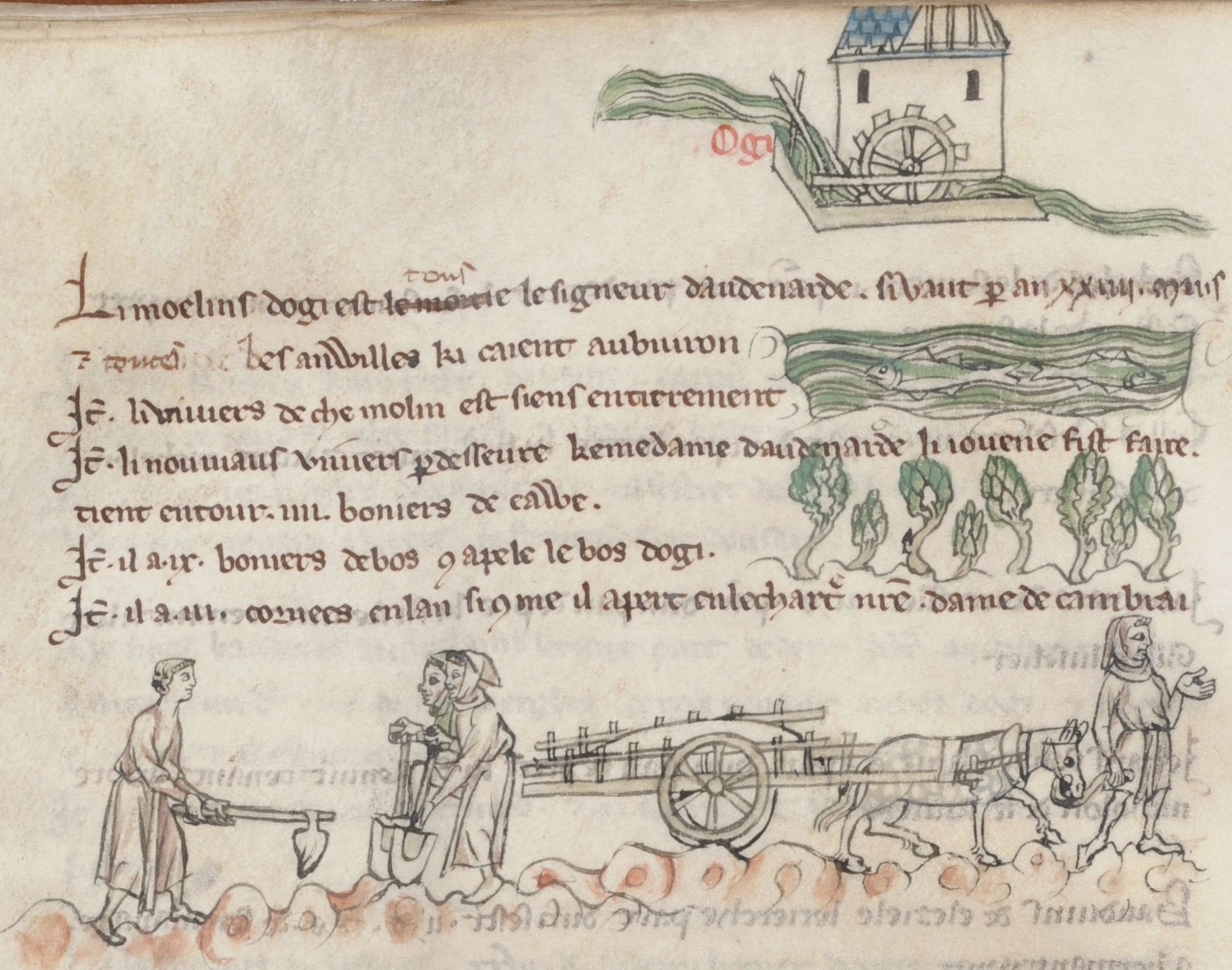

Draft of a part of the Ename map by Jan Bale (preserved at the Beaucarne House)

One of the two final maps of the abbey properties around Ename by Jan Bale (1661)

The abbey is depicted twice. First of all, it is present in the final map (see detail below) showing, for example, the timber harbour and elm driveway at the entrance and the abbey belltower containing a carillon.

Detail of the Ename map of Jan Bale depicting the abbey in 1660

Detail view on the abbey buildings on the map of Jan Bale (1661)

The second depiction, drawn on parchment, shows the front side of the abbey and is preserved in the Beaucarne House in Ename. This highly detailed drawing is very precise (as it fits very well with the excavation results) and of uttermost importance for our virtual reconstructions.

Drawing on parchment of the Ename abbey buildings in 1660 by Jan Bale (Beaucarne House)

Detail of the original drawing of the abbey by Jan Bale (Beaucarne House)

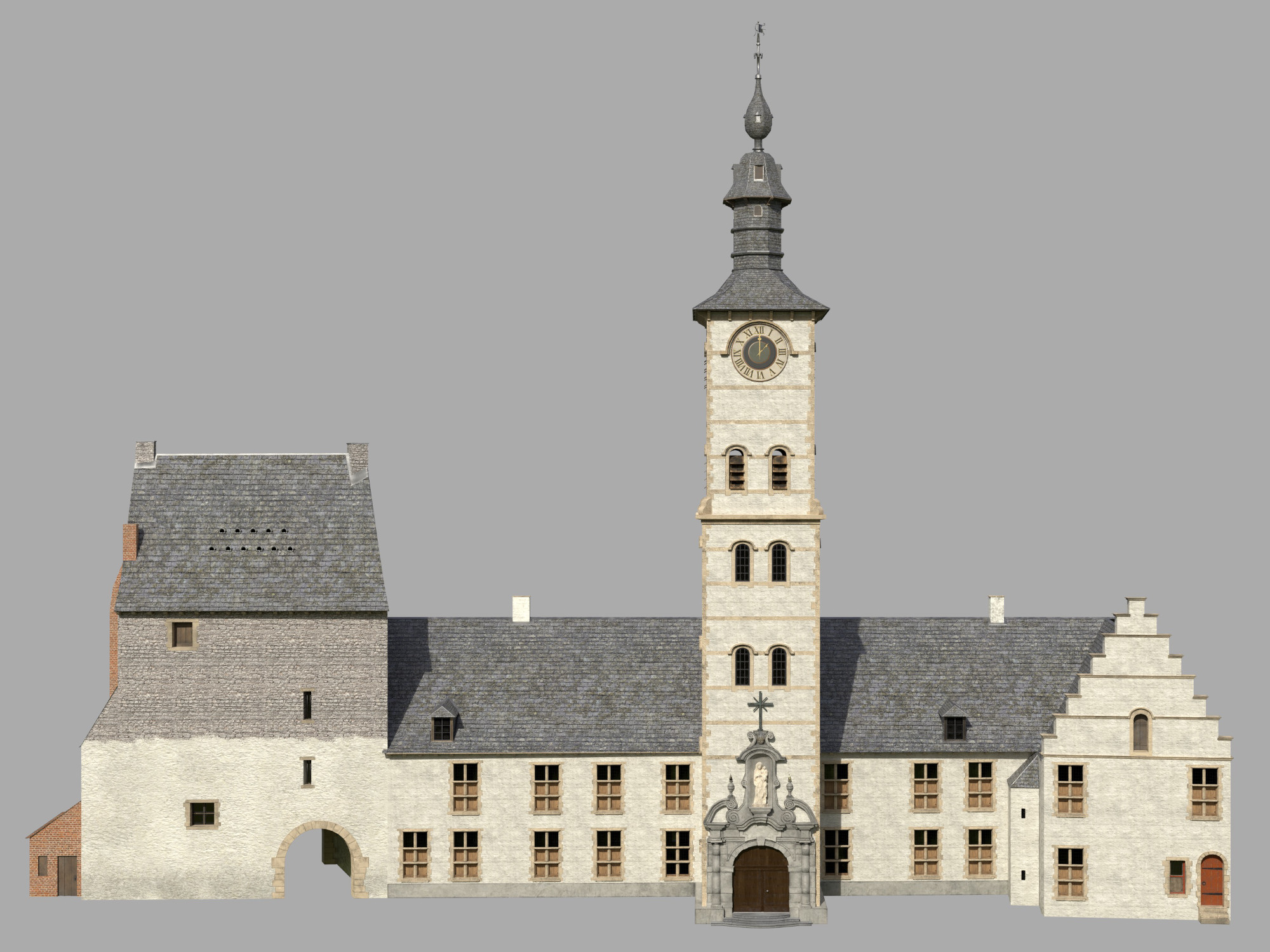

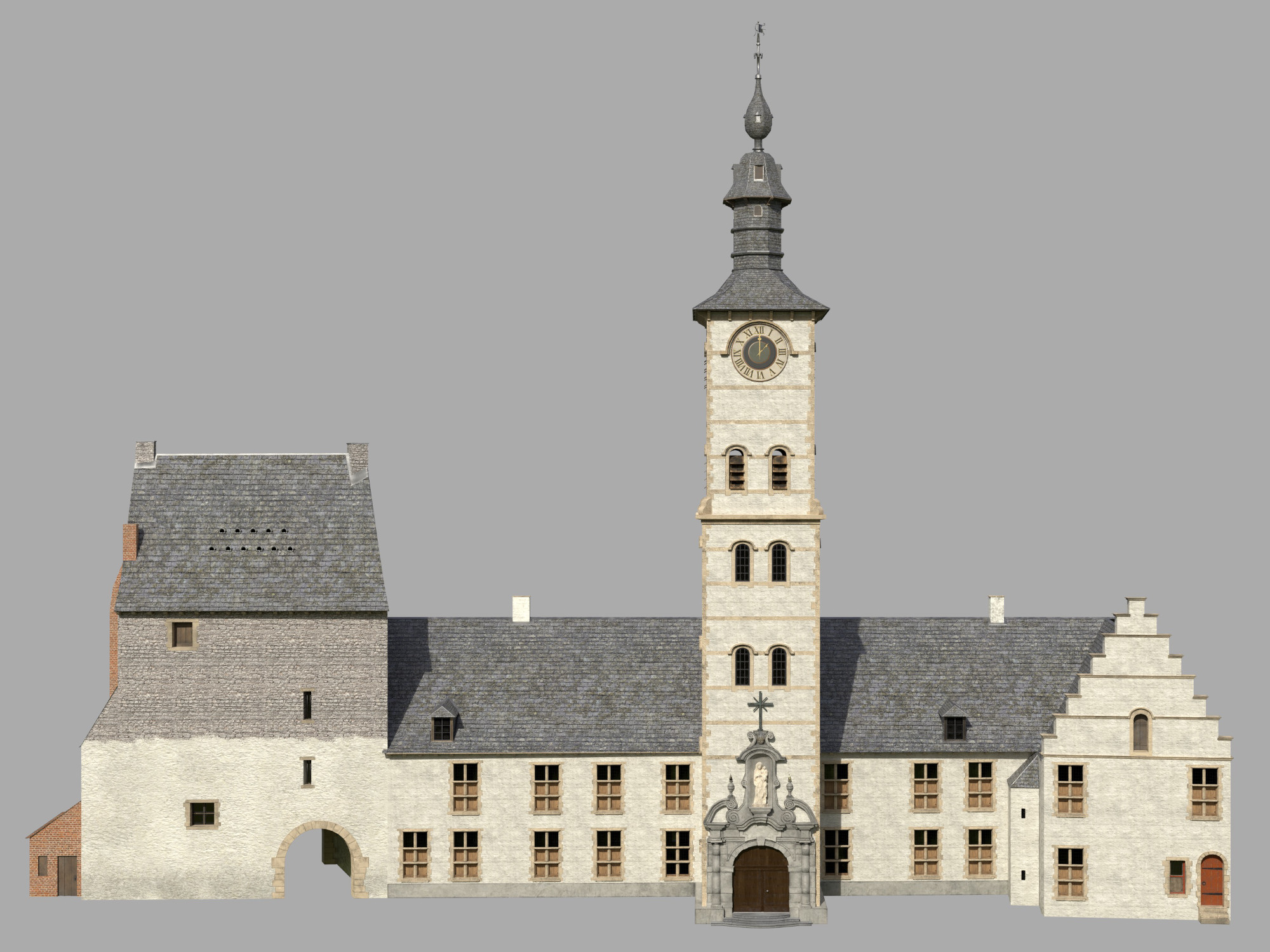

Based on these drawings and the archaeological remains that have been excavated in the period 1982 – 1995, we made a detailed virtual reconstruction of the abbot and guest quarters of the abbey, containing (see image below from left to right) the old gate and prison (with the abbey dovecote on top) , the meeting room (as depicted above), the entrance and staircase hall, the room of the doorkeeper/tailor and the former house of the abbot of which the function around 1660 is unknown (maybe house of the provost). The upper floor on the left-hand side contains the apartment of the abbot.

Virtual reconstruction of the guest quarters of the Ename abbey (3D model: Cassandre Jean)

The highly decorated baroque entrance portal gave way to a staircase hall that provided access on the left-hand side to the meeting room (see image above) downstairs, and to the apartment of the abbot upstairs. On the right-hand side, one goes to the dining room for guests (downstairs) and to the guest rooms upstairs. Above the entrance door to the staircase hall is a door to the carillon tower. The excavation results provided us with more information on the structure of the elaborated staircase.

A draft virtual reconstruction of the central staircase hall (3D model: Cassandre Jean)

The virtual reconstruction of the carillon tower still needs more work and will hold, from top to bottom, the bells, the keyboard, the clockwork with drum and the weights of the clockwork. The building of this carillon was one of the major works that abbot De Loose commissioned when being promoted to abbot in spring 1657. The bells are being cast by Pieter Hemony between September 1658 and 1660 and the carillon is fully operational before August 1665, as mentioned by Pieter Hemony in a letter to abbot De Loose.

Open 3D model of the carillon tower (3D model: Cassandre Jean) – work in progress