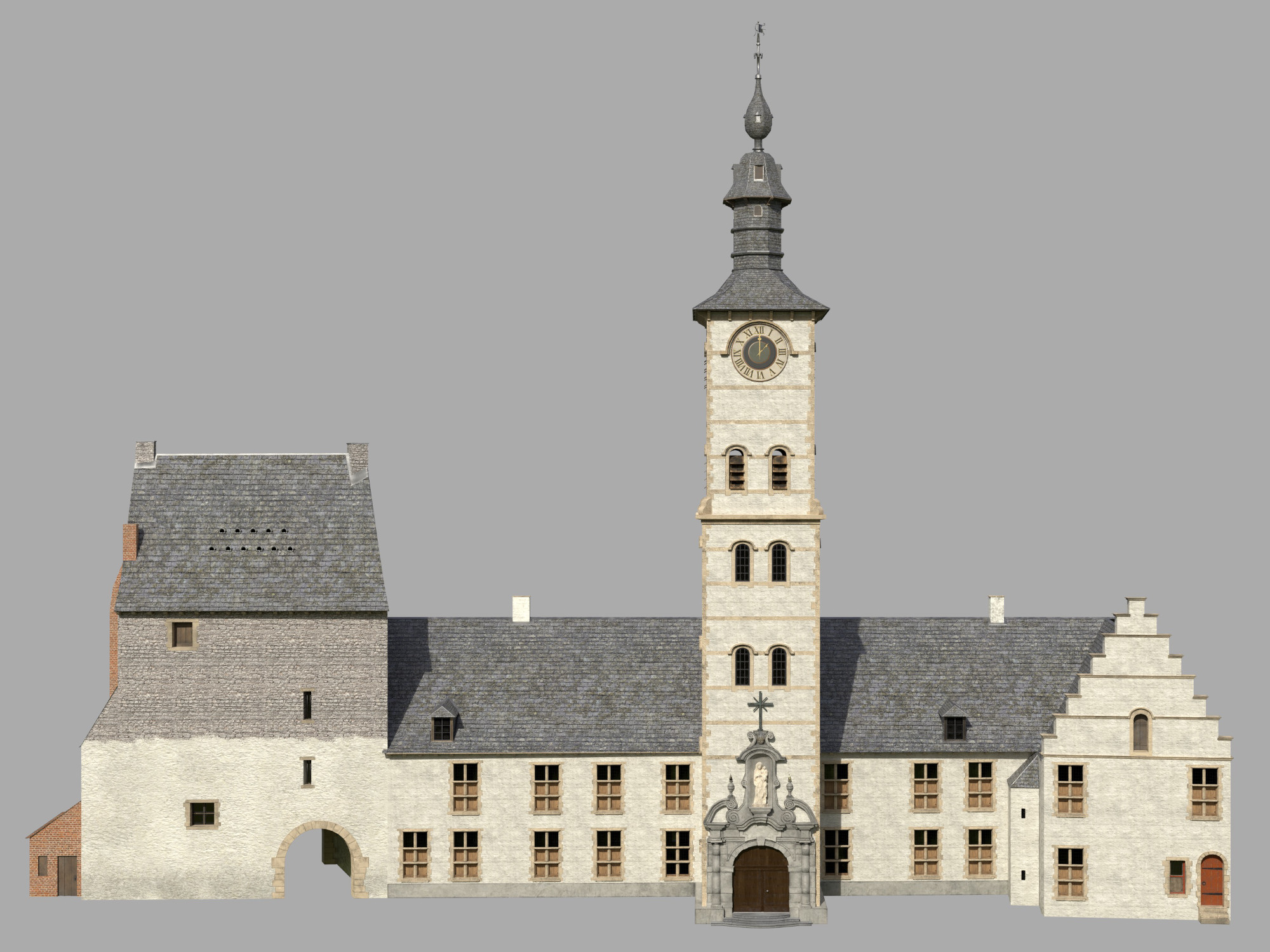

When entering the west wing through the main entrance door, one sees a statue of Our Lady holding her child Jesus. On the front view of the abbey, there is a statue depicted there and it is highly probable that it is this typical Saint Saviour depiction as it unites both denominations of the abbey: first (1063-1070) as an Our Lady abbey, after at (1070-1795) as a Saint Saviour abbey. Although this is an educated guess, it is supported by a wooden statue from the abbey, photographed by Prof. A. Vande Walle in the 1940s (the photo is preserved in the Beaucarne House and the KIK), that does show Christ as Salvator Mundi (characterised by holding the orb in the left hand and raising the right hand in blessing, like in the famous Da Vinci painting).

Under the statue, we have added the abbey motto “Diligite Alterutrum” or “Love Each Other”. Going through the portal, one enters a central staircase hall that connects to the guest rooms, a meeting room (depicted in a 1658 painting by Jan Bale), the room of the personal tailor of the abbot (acting also as doorkeeper to this west wing) and the guest’s dining room with adjacent kitchen. This central hall is described as the voorsaele by abbot De Loose in the Regulen text about the organisation of the abbey (published by Guido Tack in 1999).

On the first floor, the stairs connect to guest rooms, the rooms of the abbot (as can be read from the Regulen) and also to the carillon tower.

We have no direct information on the structure of the Ename clocktower, so we have related to other historical carillons to find examples of the structure and the different components of the carillon. We combine this with some observations that give hints about the interior of the tower (which is square, as shown by the archaeological remains). A first observation is that the tower has three floors of equal height (4 m), measuring 3,5 x 3,5 m, that have 3 x 2 windows and one top floor with 4 x 2 louvered openings that most probably contains the bells. Many clock towers and belfries do have this structure (for example the Ghent belfry).

A second observation is that the floors that have windows do not have windows on the back side, while the presumed bell chamber has openings on all sides. This brings us to the assumption that the first three floors above the entrance have a stair structure against the back wall.

When we enter the first floor of the tower, above the abbey entrance, we find the room of the weights. In this room, the weights of the clock and the carillon drum can be lowered over an additional floor. We assume three stone weights for the clock (each 40 kg) and a heavy lead weight for the carillon drum (1600 kg), which are secured – in case they might fall – by wooden boxes containing branches (for the 40 kg weights) and 6 wooden beams (for the lead weight). The breaking of the branches or beams should be sufficient to absorb the energy of the falling weight (otherwise the weight would go through the floor). The carillon of Tienen (Belgium) has also wooden beams that break when the drum weight (600 kg) would fall, while the carillon of Mechelen is using a pile of ceramic roof tiles as impact absorber.

On the next floor, we find the automated carillon, consisting of a large bronze drum, driven by the lead weight and a clockwork, consisting of a verge-and-foliot clock and ringing mechanisms for the hour and half hour, driven by three stone weights. Pendulum clocks, although invented by Christiaan Huygens in 1656, only appear in clock towers around 1690, resulting in the addition of a second hand on the clock dial to indicate the minutes.

The bronze drum (with a diameter of 110 cm) has 120 rows and 60 tracks of perforations in which metal screws can be inserted, that make levers move that are attached (through twisted copper wires) to hammers that are striking the bells (in the bell chamber above). Note that the largest bell also has a diameter of 110 cm, so the drum can be raised (when installed) or lowered (when repaired or removed) in the same way as the bells (see next post).

As this mechanical system has a certain inertia, it would be impossible to play a sequence of short notes on the same bell. Therefore, most bells are equipped with 2 or even 3 hammers to enable this.

As each hammer needs its own track on the drum, we need more tracks on the drum than the number of bells. We know from the letters of Pieter Hemony that the Ename carillon was capable of playing 1/16 notes, so most bells had multiple hammers. The system to play 1/16 notes was invented in Ghent in 1660 by father Philippe Wyckaert, in cooperation with Pieter Hemony, and already implemented in Ename before 1665. Hence, it is quite probable that Philippe Wyckaert has implemented the clock and automated carillon in Ename too.

The carillon of Ename started in 1660 with 27 bells for which 60 tracks were sufficient. We use the hypothesis that the same drum was reused in 1679 when the carillon was upgraded to 35 bells, as such drums were expensive and difficult to make. Normally, at least 68 tracks are required for 35 bells, so it is possible that the 35 bells had more than 60 hammers but that only 60 of them were connected to the drum, dependent on the music to play. When the music content changed, one could change which hammers were connected to the drum, by changing the wiring (see next post).

Programming the drum happens from the front side, with the lower notes on the left and the higher notes on the right and the drum rotating downwards. A person standing in front of the drum was adding the screws while another (small) person had to enter the drum to fix the screws from the inside. This process could take up to a few days, so the silent week before Easter was chosen to change the music on the drum. In some places, this was done more than once a year.

We assume that all weights are wound up twice a day (hence every 12 hours). The stone weights can travel over more than 6 m downwards (so they lower on the average 0,5 m/h) and use a single pulley system (hence 12 m of cable). The lead weight can travel about 5 m downwards (so the lead weight lowers at 42 cm/h) and uses a double pulley system (hence 15 m of cable).

One floor higher, we assume that the carillon keyboard was situated, one floor below the bell chamber. This assumption is based upon several factors. For optimal interaction with the bells, the wires between the keyboard and the bells should be as short as possible. On the other hand, the keyboard cannot be located in the bell chamber as it is already completely filled (as attested by Pieter Hemony in a letter to abbot De Loose that any additional bells cannot be added anymore into the bell chamber).

The orientation of the keyboard towards the centre of the tower allows to have a similar connection schema as the drum (the lower notes on the left and the higher notes on the right): this simplifies the organisation of the bells and connection of the bells to both drum and keyboard (see next post). There are 35 bells so the keyboard has 35 batons and 11 pedals, and spans 3 octaves.

We digitised our expert adviser and carillon player Luc Rombouts in 3D and turned him into his alter ego father Lucas, playing the virtual carillon (Aria from the Leuven carillon manuscript, dated 1756).